World Economic Outlook

World Economic Outlook, January 2020

January 2020

Tentative Stabilization, Sluggish Recovery?

- Global growth is projected to rise from an estimated 2.9 percent in 2019 to 3.3 percent in 2020 and 3.4 percent for 2021—a downward revision of 0.1 percentage point for 2019 and 2020 and 0.2 for 2021 compared to those in the October World Economic Outlook (WEO). The downward revision primarily reflects negative surprises to economic activity in a few emerging market economies, notably India, which led to a reassessment of growth prospects over the next two years. In a few cases, this reassessment also reflects the impact of increased social unrest.

- On the positive side, market sentiment has been boosted by tentative signs that manufacturing activity and global trade are bottoming out, a broad-based shift toward accommodative monetary policy, intermittent favorable news on US-China trade negotiations, and diminished fears of a no-deal Brexit, leading to some retreat from the risk-off environment that had set in at the time of the October WEO. However, few signs of turning points are yet visible in global macroeconomic data.

- While the baseline growth projection is weaker, developments since the fall of 2019 point to a set of risks to global activity that is less tilted to the downside compared to the October 2019 WEO. These early signs of stabilization could persist and eventually reinforce the link between still-resilient consumer spending and improved business spending. Additional support could come from fading idiosyncratic drags in key emerging markets coupled with the effects of monetary easing. Downside risks, however, remain prominent, including rising geopolitical tensions, notably between the United States and Iran, intensifying social unrest, further worsening of relations between the United States and its trading partners, and deepening economic frictions between other countries. A materialization of these risks could lead to rapidly deteriorating sentiment, causing global growth to fall below the projected baseline.

- Stronger multilateral cooperation and a more balanced policy mix at the national level, considering available monetary and fiscal space, are essential for strengthening economic activity and forestalling downside risks. Building financial resilience, strengthening growth potential, and enhancing inclusiveness remain overarching goals. Closer cross-border cooperation is needed in multiple areas, to address grievances with the rules-based trading system, curb greenhouse gas emissions, and strengthen the international tax architecture. National-level policies should provide timely demand support as needed, using both fiscal and monetary levers depending on available policy room.

Recent Developments and Implications for the Forecast

Trade policy uncertainty, geopolitical tensions, and idiosyncratic stress in key emerging market economies continued to weigh on global economic activity—especially manufacturing and trade—in the second half of 2019. Intensifying social unrest in several countries posed new challenges, as did weather-related disasters—from hurricanes in the Caribbean, to drought and bushfires in Australia, floods in eastern Africa, and drought in southern Africa.

Despite these headwinds, some indications emerged toward year-end that global growth may be bottoming out. Moreover, monetary policy easing continued into the second half of 2019 in several economies. Adding to the substantial support the easing provided earlier in 2019, its lagged effects should help global activity recover in early 2020. As discussed below, the 2019 global growth estimate and 2020 projection would have been 0.5 percentage point lower in each year without monetary stimulus.

Tentative signs of stabilization at a sluggish pace

In the third quarter of 2019, growth across emerging market economies (including India, Mexico, and South Africa) was weaker than expected at the time of the October WEO, largely due to country-specific shocks weighing on domestic demand. The advanced economy group slowed broadly as anticipated (mostly reflecting softer growth in the US after several quarters of above-trend performance). Despite continued job creation (in some cases, in the context of unemployment rates already at record lows), core consumer price inflation remained muted across advanced economies. It softened further across most emerging market economies amid more subdued activity. Weak demand lowered metals and energy prices, which kept a lid on headline inflation.

High frequency indicators for the fourth quarter tentatively suggest momentum stabilized at a sluggish pace, helped by the broad-based shift earlier in the year toward accommodative monetary policy and fiscal easing in some countries (including China, Korea, and the United States). Temporary factors that had slowed global manufacturing—auto sector adjustments to new emissions standards, a lull in the launch of new tech products, and inventory accumulation—appeared to fade. Business sentiment and the outlook of purchase managers in the manufacturing sector ceased deteriorating, but remained pessimistic overall. Importantly, the new orders subcomponent of the surveys picked up, particularly in emerging market economies. Consistent with the surveys, world trade growth appeared to be bottoming out. Service sector activity on the other hand weakened somewhat but remained in expansionary territory, supported by still-resilient consumer spending—which, in turn, helped maintain tight labor markets, low unemployment, and modestly rising wages.

Supportive financial conditions

The early signs of stabilization reinforced financial market sentiment already shored up by central bank rate cuts. Markets appeared to have internalized the outlook for US monetary policy and the Fed’s shift to “on hold” forward guidance following three rate cuts in the second half of 2019. Intermittent favorable news on US-China economic relations and diminished fears of a hard Brexit supported investors’ risk appetite. Equities continued to advance in the large advanced economies over the fall; core sovereign bond yields rose from their September low; and portfolio flows to emerging market economies strengthened, particularly to bond funds. Currency movements between September and early January reflected the general strengthening of risk sentiment and reduced trade tensions as the US dollar and the Japanese yen weakened by about 2 percent, while the Chinese renminbi gained about 1½ percent. The most notable movement across major currencies was the appreciation of the British pound (4 percent since September) on perceptions of reduced risks of a no-deal Brexit. Financial conditions thus remain broadly accommodative across advanced and emerging market economies (Box 1).

The main considerations for the global growth forecast from the backdrop of recent developments include: carryover from weaker-than anticipated second half outturns for 2019 among key emerging market economies; signs of tentative stabilization in manufacturing in the fourth quarter, but some weakening in still-resilient service sector activity; accommodative financial conditions; and uncertain prospects regarding tariffs, social unrest, and geopolitical tensions.

Global Growth Outlook: Modest Pickup in 2020

Global growth, estimated at 2.9 percent in 2019, is projected to increase to 3.3 percent in 2020 and inch up further to 3.4 percent in 2021. Compared to the October WEO forecast, the estimate for 2019 and the projection for 2020 represent 0.1 percentage point reductions for each year while that for 2021 is 0.2 percentage point lower. A more subdued growth forecast for India (discussed below) accounts for the lion’s share of the downward revisions.

The global growth trajectory reflects a sharp decline followed by a return closer to historical norms for a group of underperforming and stressed emerging market and developing economies (including Brazil, India, Mexico, Russia, and Turkey). The growth profile also relies on relatively healthy emerging market economies maintaining their robust performance even as advanced economies and China continue to slow gradually toward their potential growth rates. The effects of substantial monetary easing across advanced and emerging market economies in 2019 are expected to continue working their way through the global economy in 2020. The global growth estimate for 2019 and projection for 2020 would have been 0.5 percentage point lower in each year without this monetary stimulus. The global recovery is projected to be accompanied by a pickup in trade growth (albeit more modest than forecast in October), reflecting a recovery in domestic demand and investment in particular, as well as the fading of some temporary drags in the auto and tech sectors.

These outcomes depend to an important extent on avoiding further escalation in the US-China trade tensions (and, more broadly, on preventing a further worsening of US-China economic relations, including around tech supply chains), averting a no-deal Brexit, and the economic ramifications of social unrest and geopolitical tensions remaining contained.

Across advanced economies, growth is projected to stabilize at 1.6 percent in 2020–21 (0.1 percentage point lower than in the October WEO for 2020, mostly due to downward revisions for the United States, euro area and the United Kingdom, and downgrades to other advanced economies in Asia, notably Hong Kong SAR following protests).

- In the United States, growth is expected to moderate from 2.3 percent in 2019 to 2 percent in 2020 and decline further to 1.7 percent in 2021 (0.1 percentage point lower for 2020 compared to the October WEO). The moderation reflects a return to a neutral fiscal stance and anticipated waning support from further loosening of financial conditions.

- Growth in the euro area is projected to pick up from 1.2 percent in 2019 to 1.3 percent in 2020 (a downward revision of 0.1 percentage point) and 1.4 percent in 2021. Projected improvements in external demand support the anticipated firming of growth. The October 2019 WEO projections for France and Italy remain unchanged, but the projections have been marked down for 2020 in Germany, where manufacturing activity remains in contractionary territory in late 2019, and for Spain due to carryover from stronger-than-expected deceleration in domestic demand and exports in 2019.

- In the United Kingdom, growth is expected to stabilize at 1.4 percent in 2020 and firm up to 1.5 percent in 2021—unchanged from the October WEO. The growth forecast assumes an orderly exit from the European Union at the end of January followed by a gradual transition to a new economic relationship.

- Japan’s growth rate is projected to moderate from an estimated 1 percent in 2019 to 0.7 percent in 2020 (0.1 and 0.2 percentage point higher than in the October WEO). The upward revision to estimated 2019 growth reflects healthy private consumption, supported in part by government countermeasures that accompanied the October increase in the consumption tax rate, robust capital expenditure, and historical revisions to national accounts. The upgrade to the 2020 growth forecast reflects the anticipated boost from the December 2019 stimulus measures. Growth is expected to decline to 0.5 percent (close to potential) in 2021, as the impact of fiscal stimulus fades.

For the emerging market and developing economy group, growth is expected to increase to 4.4 percent in 2020 and 4.6 percent in 2021 (0.2 percentage point lower for both years than in the October WEO) from an estimated 3.7 percent in 2019. The growth profile for the group reflects a combination of projected recovery from deep downturns for stressed and underperforming emerging market economies and an ongoing structural slowdown in China.

- Growth in emerging and developing Asia is forecast to inch up slightly from 5.6 percent in 2019 to 5.8 percent in 2020 and 5.9 percent in 2021 (0.2 and 0.3 percentage point lower for 2019 and 2020 compared to the October WEO). The growth markdown largely reflects a downward revision to India’s projection, where domestic demand has slowed more sharply than expected amid stress in the nonbank financial sector and a decline in credit growth. India’s growth is estimated at 4.8 percent in 2019, projected to improve to 5.8 percent in 2020 and 6.5 percent in 2021 (1.2 and 0.9 percentage point lower than in the October WEO), supported by monetary and fiscal stimulus as well as subdued oil prices. Growth in China is projected to inch down from an estimated 6.1 percent in 2019 to 6.0 percent in 2020 and 5.8 percent in 2021. The envisaged partial rollback of past tariffs and pause in additional tariff hikes as part of a “Phase One” trade deal with the United States is likely to alleviate near-term cyclical weakness, resulting in a 0.2 percentage point upgrade to China’s 2020 growth forecast relative to the October WEO. However, unresolved disputes on broader US-China economic relations as well as needed domestic financial regulatory strengthening are expected to continue weighing on activity. After slowing to 4.7 percent in 2019, growth in ASEAN-5 countries is projected to remain stable in 2020 before picking up in 2021. Growth prospects have been revised down slightly for Indonesia and Thailand, where continued weakness in exports is also weighing on domestic demand.

- Growth in emerging and developing Europe is expected to strengthen to around 2.5 percent in 2020–21 from 1.8 percent in 2019 (0.1 percentage point higher for 2020 than in the October WEO). The improvement reflects continued robust growth in central and eastern Europe, a pickup in activity in Russia, and ongoing recovery in Turkey as financing conditions turn less restrictive.

- In Latin America, growth is projected to recover from an estimated 0.1 percent in 2019 to 1.6 percent in 2020 and 2.3 percent in 2021 (0.2 and 0.1 percentage point weaker respectively than in the October WEO). The revisions are due to a downgrade to Mexico’s growth prospects in 2020-21, including due to continued weak investment, as well as a sizable markdown in the growth forecast for Chile, affected by social unrest. These revisions are partially offset by an upward revision to the 2020 forecast for Brazil, owing to improved sentiment following the passage of pension reform and the fading of supply disruptions in the mining sector.

- Growth in the Middle East and Central Asia region is expected at 2.8 percent in 2020 (0.1 percentage point lower than in the October WEO), firming up to 3.2 percent in 2021. The downgrade for 2020 mostly reflects a downward revision to Saudi Arabia’s projection on expected weaker oil output growth following the OPEC+ decision in December to extend supply cuts. Prospects for several economies remain subdued owing to rising geopolitical tensions (Iran), social unrest (including in Iraq and Lebanon), and civil strife (Libya, Syria, Yemen).

- In sub-Saharan Africa, growth is expected to strengthen to 3.5 percent in 2020–21 (from 3.3 percent in 2019). The projection is 0.1 percentage point lower than in the October WEO for 2020 and 0.2 percentage point weaker for 2021. This reflects downward revisions for South Africa (where structural constraints and deteriorating public finances are holding back business confidence and private investment) and for Ethiopia (where public sector consolidation, needed to contain debt vulnerabilities, is expected to weigh on growth).

Risks to the Outlook

The balance of risks to the global outlook remains on the downside, but less skewed toward adverse outcomes than in the October WEO. The early signs of stabilization discussed above could persist, leading to favorable dynamics between still-resilient consumer spending and improved business spending. Additional support could come from fading idiosyncratic drags in key emerging markets coupled with the effects of monetary easing and improved sentiment following the “Phase One” US-China trade deal, with the associated partial rollback of previously implemented tariffs and a truce on new tariffs. A confluence of these factors could lead to a stronger recovery than currently projected.

Nonetheless, downside risks remain prominent.

- Rising geopolitical tensions, notably between the United States and Iran, could disrupt global oil supply, hurt sentiment, and weaken already tentative business investment. Moreover, intensifying social unrest across many countries—reflecting, in some cases, the erosion of trust in established institutions and lack of representation in governance structures—could disrupt activity, complicate reform efforts and weaken sentiment, dragging growth lower than projected. Where these pressures compound ongoing deep slowdowns, for example among stressed and underperforming emerging market economies, the anticipated pickup in global growth—driven almost entirely by the projected improvement (in some cases, shallower contractions) for these economies—would fail to materialize.

- Higher tariff barriers between the United States and its trading partners, notably China, have hurt business sentiment and compounded cyclical and structural slowdowns underway in many economies over the past year. The disputes have extended to technology, imperiling global supply chains. The rationale for protectionist acts has expanded to include national security or currency grounds. Prospects for a durable resolution to trade and technology tensions remain elusive, despite sporadic favorable news on ongoing negotiations. Further deterioration in economic relations between the United States and its trading partners (seen, for example, in frictions between the United States and the European Union), or in trade ties involving other countries, could undermine the nascent bottoming out of global manufacturing and trade, leading global growth to fall short of the baseline.

- A materialization of any of these risks could trigger rapid shifts in financial sentiment, portfolio reallocations toward safe assets, and rising rollover risks for vulnerable corporate and sovereign borrowers. A widespread tightening of financial conditions would expose the financial vulnerabilities that have built up over years of low interest rates and further curtail spending on machinery, equipment, and household durables. The resulting renewed weakness in manufacturing could eventually spread to services and lead to a broader slowdown.

- Weather-related disasters such as tropical storms, floods, heatwaves, droughts, and wildfires have imposed severe humanitarian costs and livelihood loss across multiple regions in recent years. Climate change, the driver of the increased frequency and intensity of weather-related disasters, already endangers health and economic outcomes, and not only in the directly affected regions. It could pose challenges to other areas that may not yet feel the direct effects, including by contributing to cross-border migration or financial stress (for instance, in the insurance sector). A continuation of the trends could inflict even bigger losses across more countries.

Policy Priorities

The risk of protracted subpar global growth remains tangible despite tentative signs of stabilizing momentum. Policy missteps at this stage would further enfeeble an already weak global economy. Instead, stronger multilateral cooperation and national-level policies that provide timely support could foster a sustained recovery to the benefit of all. Across all economies, a key imperative—increasingly relevant at a time of widening unrest—is to enhance inclusiveness, ensure that safety nets are indeed protecting the vulnerable, and governance structures strengthen social cohesion.

Multilateral cooperation. Closer cross-border cooperation is needed on multiple fronts. Countries should expeditiously address grievances with the rules-based trading system, promptly resolve the impasse over the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body, and settle disagreements without raising tariffs and non-tariff barriers. Technology tensions between countries are unlikely to be resolved unless they cooperate to curtail cross-border cyberattacks and solve outstanding issues concerning intellectual property rights and technology transfer. Failure to work out trade and technology conflicts will undermine confidence further, weaken investment, and lead to rising job losses; over a longer horizon, this would inhibit productivity growth and slow increases in living standards. Countries urgently need to cooperate on curbing greenhouse gas emissions and limiting the rise of global temperature with an approach that ensures appropriate burden-sharing across and within borders. Other areas where stronger cooperation would help enhance inclusiveness and resilience include reducing cross-border tax evasion and corruption; avoiding a rollback of global financial regulatory reforms; and ensuring an adequately resourced global financial safety net.

Policy priorities for advanced economies. Considering the modest growth potential across the group, countries with fiscal space should increase spending on initiatives that raise productivity growth, including research, training, and physical infrastructure. Barring where private demand is very weak, high debt countries should generally consolidate to prepare for the next downturn and looming entitlement spending further down the road. With policy rates in many advanced economies close to the effective lower bound and long-term interest rates at low (in some cases, negative) levels, the room for monetary policy to combat further growth declines is limited. Countries with fiscal space, and where fiscal policy is not already excessively expansionary, can rely more on fiscal stimulus to support demand if the need arises. Policymakers would be well-placed to counter the next downturn if they prepare in advance a contingent response. The strategy should feature an important role for investment in mitigating climate change as well as in areas that strengthen potential growth and ensure the gains are widely shared, including education, health, workforce skills, and infrastructure. Countries that need to ensure their debt remains sustainable have less room for maneuver. Should activity weaken substantially, and if market conditions permit, they can slow the pace of fiscal consolidation to avoid an extended period of growth below potential. Across all economies, measures that address structural constraints and increase labor force participation rates remain essential to counter population aging, strengthen the medium-term outlook, and build resilience. Countries should also ensure that their social safety nets facilitate broad access to opportunities and lower economic insecurity. Stronger macroprudential policies, more proactive supervision, and, in some cases, further clean-up of bank balance sheets are critical, especially as vulnerabilities continue accumulating in an extended period of low interest rates.

Policy priorities for emerging market and developing economies. Within the group, policy priorities differ based on specific circumstances. Emerging market economies in macroeconomic distress related to domestic imbalances will need to continue making the policy adjustments necessary for rebuilding confidence and putting in place the conditions for a return to stable and sustainable growth. In these contexts, ensuring adequate safety nets to protect the vulnerable remains critical within overall existing constraints. High-debt economies should generally aim for consolidation—calibrating its pace to avoid a sharp slowdown in activity—by improving subsidy targeting, broadening the revenue base, and ensuring stronger compliance. This consolidation would create space for combating downturns and investing in development needs, especially relevant in low-income developing countries for progressing toward the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Countries with generally more secure conditions, but where activity has weakened relative to potential, can take advantage of the recent decline in inflation to deploy further monetary support, especially where real interest rates remain high. Ensuring financial resilience, through maintaining adequate capital and liquidity buffers while minimizing currency and maturity mismatches, continues to be a key imperative, particularly with the low level of interest rates in advanced economies and possible search for yield elsewhere. Across the group, an overarching shared objective is to make growth more inclusive through spending on health and education to raise human capital, while at the same time incentivizing entry of firms that create high value-added jobs and gainfully employ wider segments of the population.

|

Table 1. Overview of the World Economic Outlook Projections |

|||||||||||

|

(Percent change, unless noted otherwise) |

|||||||||||

|

Year over Year |

|||||||||||

|

Difference from Oct 2019 |

Q4 |

over Q4 2/ |

|||||||||

|

Estimate |

Projections |

WEO Projections 1/ |

Estimate |

Projections |

|||||||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2020 |

2021 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|||

|

World Output |

3.6 |

2.9 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

–0.1 |

–0.2 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

||

|

Advanced Economies |

2.2 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

||

|

United States |

2.9 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

1.7 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

||

|

Euro Area |

1.9 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

||

|

Germany |

1.5 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

||

|

France |

1.7 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

||

|

Italy |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

–0.1 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

||

|

Spain |

2.4 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

–0.2 |

–0.1 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

||

|

Japan |

0.3 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

1.8 |

–0.3 |

||

|

United Kingdom |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

||

|

Canada |

1.9 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

||

|

Other Advanced Economies 3/ |

2.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

–0.1 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies |

4.5 |

3.7 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

–0.2 |

–0.2 |

4.0 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

||

|

Emerging and Developing Asia |

6.4 |

5.6 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

–0.2 |

–0.3 |

5.3 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

||

|

China |

6.6 |

6.1 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

0.2 |

–0.1 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

5.8 |

||

|

India 4/ |

6.8 |

4.8 |

5.8 |

6.5 |

–1.2 |

–0.9 |

4.3 |

6.9 |

6.1 |

||

|

ASEAN-5 5/ |

5.2 |

4.7 |

4.8 |

5.1 |

–0.1 |

–0.1 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

5.1 |

||

|

Emerging and Developing Europe |

3.1 |

1.8 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

||

|

Russia |

2.3 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

2.4 |

||

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

1.1 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

–0.2 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

2.4 |

||

|

Brazil |

1.3 |

1.2 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

0.2 |

–0.1 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.4 |

||

|

Mexico |

2.1 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

–0.3 |

–0.3 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

||

|

Middle East and Central Asia |

1.9 |

0.8 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Saudi Arabia |

2.4 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

–0.3 |

0.0 |

–0.9 |

2.7 |

2.2 |

||

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

–0.1 |

–0.2 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Nigeria |

1.9 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

South Africa |

0.8 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

–0.3 |

–0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

||

|

Memorandum |

|||||||||||

|

Low-Income Developing Countries |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

0.0 |

–0.1 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

World Growth Based on Market Exchange Rates |

3.0 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

||

|

World Trade Volume (goods and services) 6/ |

3.7 |

1.0 |

2.9 |

3.7 |

–0.3 |

–0.1 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Advanced Economies |

3.2 |

1.3 |

2.2 |

3.1 |

–0.4 |

–0.1 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies |

4.6 |

0.4 |

4.2 |

4.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Commodity Prices (U.S. dollars) |

|||||||||||

|

Oil 7/ |

29.4 |

–11.3 |

–4.3 |

–4.7 |

1.9 |

–0.1 |

–10.9 |

–1.5 |

–2.7 |

||

|

Nonfuel (average based on world commodity import weights) |

1.6 |

0.9 |

1.7 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

–0.7 |

4.8 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

||

|

Consumer Prices |

|||||||||||

|

Advanced Economies 8/ |

2.0 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

–0.1 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

||

|

Emerging Market and Developing Economies 9/ |

4.8 |

5.1 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

–0.2 |

0.0 |

5.1 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

||

|

London Interbank Offered Rate (percent) |

|||||||||||

|

On U.S. Dollar Deposits (six month) |

2.5 |

2.3 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

–0.1 |

–0.2 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

On Euro Deposits (three month) |

–0.3 |

–0.4 |

–0.4 |

–0.4 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

On Japanese Yen Deposits (six month) |

0.0 |

0.0 |

–0.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

. . . |

. . . |

. . . |

||

|

Note: Real effective exchange rates are assumed to remain constant at the levels prevailing during October 14-November 11, 2019. Economies are listed on the basis of economic size. The aggregated quarterly data are seasonally adjusted. WEO = World Economic Outlook. |

|||||||||||

Box 1. Global Financial Conditions: Still Accommodative

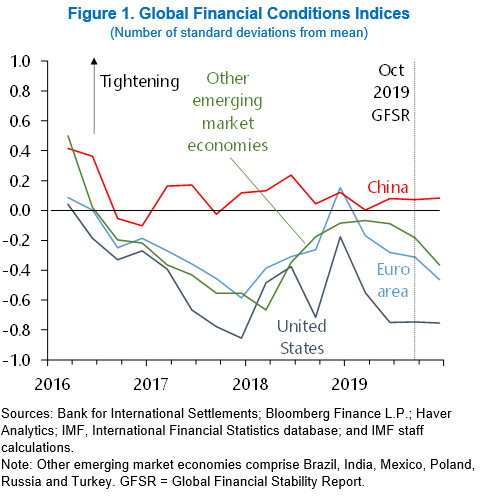

Global financial conditions continue to be accommodative by historical standards. Overall conditions are little changed since the October 2019 Global Financial Stability Report, though there has been an easing in conditions in some individual economies (Figure 1).

Over the past three months, markets have again been driven by two main factors: monetary policy and investor perceptions about trade tensions. Monetary policy has remained supportive. For example, the US Federal Reserve cut its policy rate by 25 basis points; the European Central Bank restarted net asset purchases at a pace of €20 billion per month; the People’s Bank of China reduced its medium-term lending facility rate by 5 basis points; in Turkey, the central bank cut its policy rate by 450 basis points; while the central banks in Russia and Brazil reduced their interest rates by 75 and 100 basis points, respectively.

On trade tensions, the market has oscillated back and forth according to the latest trade-related news, including the recent announcement of a “Phase One” agreement on trade between the United States and China. On net, world equity markets have risen by about 8 percent over the past three months and long-term yields in the euro area, Japan and United States have increased by 15–30 basis points from very low levels.

These developments have left US financial conditions unchanged on net. Increased corporate valuations, on the back of higher equity markets and tighter corporate bond spreads, were broadly offset by the rise in long-term yields. The level of financial conditions, however, remains accommodative.

Financial conditions in the euro area have continued to ease. This follows a combination of higher equity prices and tighter corporate bond spreads.

Turning to emerging market economies, financial conditions remained broadly unchanged in China, though corporate valuations rose.

In other emerging market economies—which in this box comprises Brazil, India, Mexico, Poland, Russia, and Turkey—aggregate conditions continued to ease further. This is largely the result of further declines in interest rates and external borrowing costs. Average sovereign spreads for this group of economies have fallen by almost 25 basis points, and corporate bond spreads have tightened by a similar amount.